In the last post(/mcp-intro), we covered why MCP matters—the Integration Tax, the USB-C analogy, the ecosystem. But we glossed over the how.

If you’re the type who needs to understand what’s actually happening before you trust a protocol, this one’s for you. We’re going deep on the architecture, the message format, and the transport layers. No hand-waving.

Fair warning: this gets technical. But by the end, you’ll understand MCP well enough to read the spec—or build your own server.

![The MCP Protocol Stack]

The Three Participants

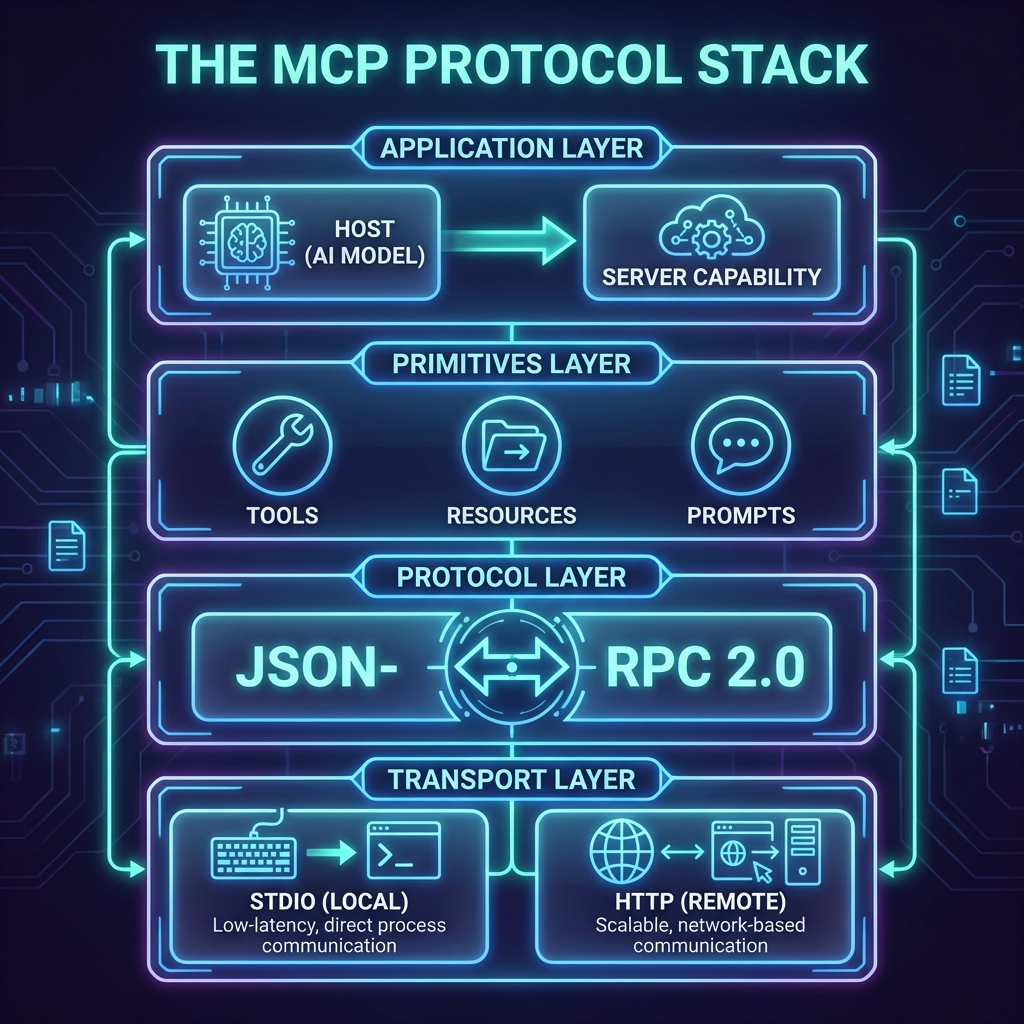

Let’s start with the cast of characters. MCP has three participants, and understanding their roles is half the battle.

Host

The Host is the AI application your user interacts with. Think Claude Desktop, Cursor, Windsurf, or your custom-built agent.

The Host is responsible for:

- Managing connections to MCP Servers (via Clients)

- Deciding which tools to call and when

- Handling user consent and security policies

- Orchestrating the overall workflow

Crucially, the Host contains the LLM. It’s the “brain” that decides what to do. The Servers are just the hands and eyes.

Client

The Client lives inside the Host. It’s the protocol translator—the thing that speaks MCP.

Each Client maintains a 1:1 connection with a single Server. If your Host connects to Slack, GitHub, and Postgres, it runs three Clients internally, one for each.

The Client handles:

- Protocol negotiation (what version of MCP? what capabilities?)

- Message framing and transport

- Translating LLM requests into MCP messages

You don’t usually build Clients from scratch. The SDKs handle this. But understanding the distinction matters when debugging.

Server

The Server is where the magic happens. It exposes capabilities—Tools, Resources, Prompts—to the Client.

Servers can be:

- Local: Running on your machine, communicating via stdio

- Remote: Running on a cloud server, communicating via HTTP

A single Server might expose a database, an API, a filesystem, or all three. The protocol doesn’t care. It just asks: “What can you do?”

The Connection Lifecycle

Here’s what happens when a Host connects to a Server.

1. Transport Initialization

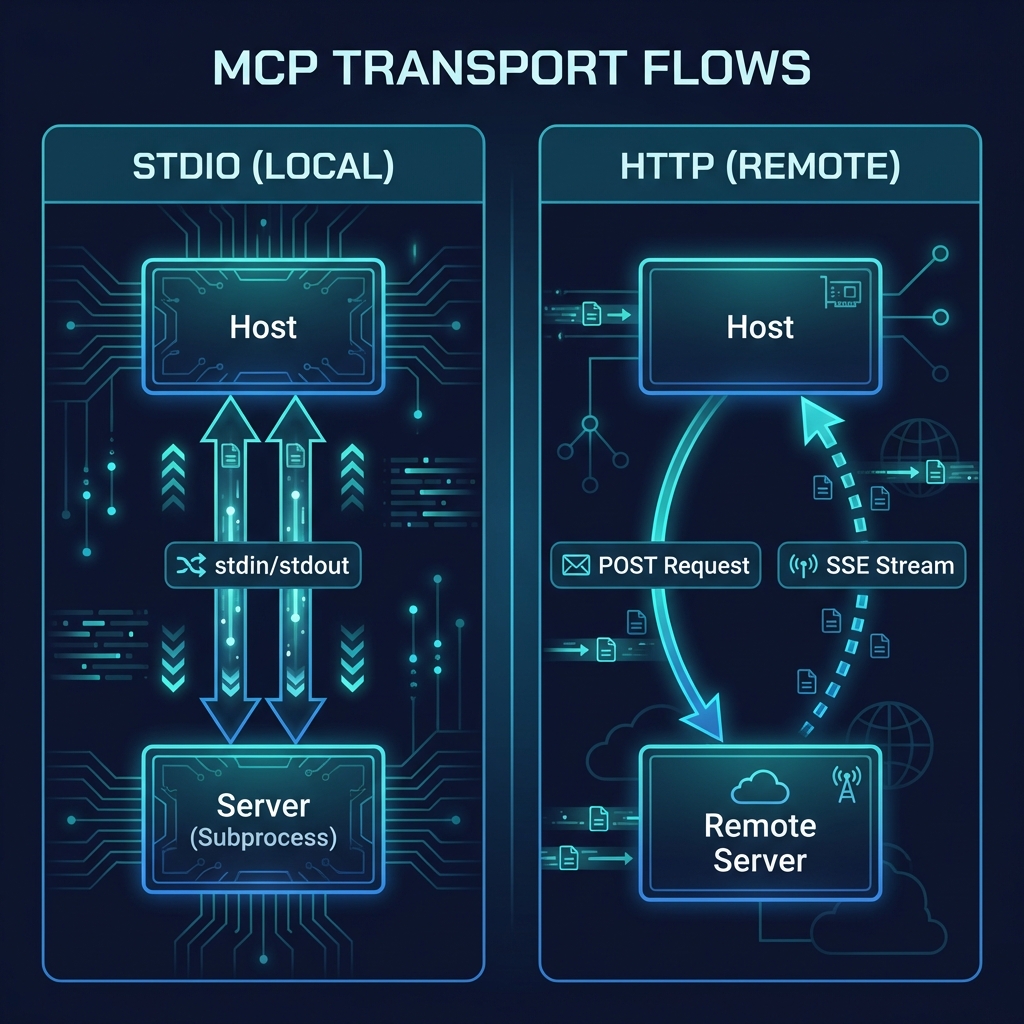

First, the transport layer establishes a connection. MCP supports two transports:

| Transport | Use Case | How It Works |

| Stdio | Local servers | The Host spawns the Server as a subprocess. Messages flow via stdin/stdout. |

| Streamable HTTP | Remote servers | The Client sends HTTP POST requests. The Server can stream responses via SSE. |

![MCP Transport Flows]

| Transport | Use Case | Security Model |

| Stdio | Local servers | Implicit Trust: Host spawns the process, so it trusts the code. |

| Streamable HTTP | Remote servers | Zero Trust: Requires OAuth 2.1 authentication and explicit authorization. |

Stdio is dead simple—no network, no ports, no authentication headaches. It’s the default for local development.

Streamable HTTP is for production deployments. It scales horizontally but demands a stricter security posture using OAuth 2.1.

2. Protocol Handshake

Once the transport is up, the Client sends an initialize request:

{

“jsonrpc”: “2.0”,

“id”: 1,

“method”: “initialize”,

“params”: {

“protocolVersion”: “2024-11-05”,

“capabilities”: {

“roots”: { “listChanged”: true },

“sampling”: {}

},

“clientInfo”: {

“name”: “MyAIApp”,

“version”: “1.0.0”

}

}

}

The Server responds with its own capabilities:

{

“jsonrpc”: “2.0”,

“id”: 1,

“result”: {

“protocolVersion”: “2024-11-05”,

“capabilities”: {

“tools”: {},

“resources”: { “subscribe”: true },

“prompts”: {}

},

“serverInfo”: {

“name”: “SlackServer”,

“version”: “2.0.0”

}

}

}

This handshake establishes:

- Which protocol version they’re using

- What capabilities each side supports

- Basic identity information

3. Initialized Notification

After the handshake, the Client sends an initialized notification to signal it’s ready. No response expected—just a “we’re good to go.”

{

“jsonrpc”: “2.0”,

“method”: “notifications/initialized”

}

Now the connection is live. The Host can start querying for tools, resources, and prompts.

The Protocol: JSON-RPC 2.0

Under the hood, MCP is just JSON-RPC 2.0. If you’ve worked with LSP (Language Server Protocol), this will feel familiar.

NOTE: Why JSON-RPC?

Why not REST or gRPC? Because JSON-RPC is stateful and bidirectional. The Server needs to send notifications (like “this resource changed”) just as much as the Client needs to send requests. It’s essentially a conversation, not just a series of GET/POST calls.

Every message is one of three types:

| Type | Has ID? | Expects Response? | Example |

| Request | Yes | Yes | tools/call, resources/read |

| Response | Yes (matches request) | No | Result or error |

| Notification | No | No | notifications/initialized |

Requests get responses. Notifications are fire-and-forget. Simple.

The Three Primitives (Deep Dive)

In Blog 1, we introduced Tools, Resources, and Prompts. Let’s go deeper.

Tools: The “Do” Layer

Tools are executable functions. When the LLM decides to take an action, it calls a Tool.

A Server advertises its Tools via tools/list:

{

“tools”: [

{

“name”: “send_message”,

“description”: “Send a message to a Slack channel”,

“inputSchema”: {

“type”: “object”,

“properties”: {

“channel”: { “type”: “string” },

“text”: { “type”: “string” }

},

“required”: [“channel”, “text”]

}

}

]

}

The Host calls a Tool via tools/call:

{

“method”: “tools/call”,

“params”: {

“name”: “send_message”,

“arguments”: {

“channel”: “#general”,

“text”: “Hello from MCP!”

}

}

}

The Server executes the function and returns a result. That’s it.

Key insight: The inputSchema uses JSON Schema. This isn’t just for documentation—it allows the LLM to validate its own calls. If the model tries to send a number where a string is required, it can catch that error before even sending the request to the server.

Resources: The “Read” Layer

Resources are data sources. Unlike Tools (which do things), Resources provide information.

Each Resource has a URI:

- file:///users/me/report.pdf

- slack://channels/general/messages

- postgres://mydb/users?limit=100

The URI scheme is up to the Server. MCP doesn’t care what it looks like—it just needs to be unique and consistent.

Clients fetch Resources via resources/read:

{

“method”: “resources/read”,

“params”: {

“uri”: “slack://channels/general/messages”

}

}

Resources can also be subscribed to. If a Resource supports subscriptions, the Server will push updates when the data changes. Useful for real-time contexts like chat messages or file watchers.

Prompts: The “Ask” Layer

Prompts are reusable interaction templates. Think of them as pre-built workflows the user can invoke.

A Server might expose a Prompt like:

{

“name”: “summarize-channel”,

“description”: “Summarize recent activity in a Slack channel”,

“arguments”: [

{

“name”: “channel”,

“description”: “The channel to summarize”,

“required”: true

},

{

“name”: “timeframe”,

“description”: “How far back to look (e.g., ’24h’, ‘7d’)”,

“required”: false

}

]

}

When invoked, the Prompt returns a structured message that guides the LLM’s response. It’s like giving the model a script to follow.

Prompts are optional—many servers don’t use them. But they’re powerful for standardizing complex workflows.

Transport Deep Dive

Let’s get specific about how messages actually move.

Stdio Transport

For local servers, MCP uses standard input/output. The Host spawns the Server as a child process and communicates via stdin/stdout.

Why stdio?

- Zero configuration: No ports, no network stack

- Secure by default: No external access possible

- Dead simple: Works on every OS

The messages are newline-delimited JSON. Send a JSON object, add a newline, done.

Streamable HTTP Transport

For remote servers, MCP uses HTTP with optional Server-Sent Events (SSE).

Client → Server: Regular HTTP POST requests with JSON body.

Server → Client: Either a direct JSON response, or an SSE stream for long-running operations.

Authentication uses OAuth 2.1 with PKCE. The spec follows RFC 9728 for discovery, so clients can automatically find the authorization server.

POST /mcp HTTP/1.1

Host: mcp.example.com

Authorization: Bearer eyJhbGciOiJS…

Content-Type: application/json

{“jsonrpc”: “2.0”, “method”: “tools/call”, …}

This transport is designed for production. It scales horizontally, works behind load balancers, and integrates with existing auth infrastructure.

Capability Negotiation

Not every Client supports every feature. Not every Server exposes every primitive.

During the handshake, both sides declare their capabilities:

Client capabilities might include:

- sampling: Can the Server request LLM completions?

- elicitation: Can the Server ask the user for input?

- roots: Does the Client expose workspace boundaries?

Server capabilities might include:

- tools: Server exposes Tools

- resources: Server exposes Resources

- prompts: Server exposes Prompts

- logging: Server can send log messages

If a Server declares “tools”: {}, the Client knows it can call tools/list and tools/call. If it doesn’t, those methods will fail.

This is how MCP stays extensible. New capabilities can be added without breaking old implementations.

Real-World Example: The Flow

Let’s trace a complete flow. User asks Claude: “What’s the latest message in #engineering?”

1. Claude (Host) decides it needs Slack data

2. Claude’s Slack Client sends resources/read with URI slack://channels/engineering/messages?limit=1

3. Slack Server fetches the message from Slack’s API

4. Slack Server returns the message content

5. Claude incorporates the message into its response

6. User sees the answer

Total round-trips: 1 (assuming the connection is already established).

If Claude instead wanted to send a message, it would use tools/call with the send_message tool. Same flow, different primitive.

What’s Next

You now understand how MCP works at the protocol level. You know the participants, the message format, the transport layers, and the capability system.

In Blog 3, we’ll put this knowledge to use. We’re building an MCP server from scratch—Python or TypeScript, your choice. You’ll have a working server in 20 minutes.

This is the first post in a series on MCP. Here’s what’s coming:

1. ✅ This Post: Why MCP matters

2. ✅ Blog 2: Under the Hood—deep dive into architecture, transports, and the protocol spec

3. Blog 3: Build Your First MCP Server in 20 minutes (Python/TypeScript)

4. Blog 4: MCP in the Wild—real-world patterns and use cases

5. Blog 5: Security, OAuth, and the agentic future

The Integration Tax era is ending. The question isn’t if MCP becomes the standard—it’s how fast you get on board.

—

Spec reference: [modelcontextprotocol.io/specification](https://modelcontextprotocol.io/specification/2025-11-25)

– Satyajeet Shukla

AI Strategist & Solutions Architect