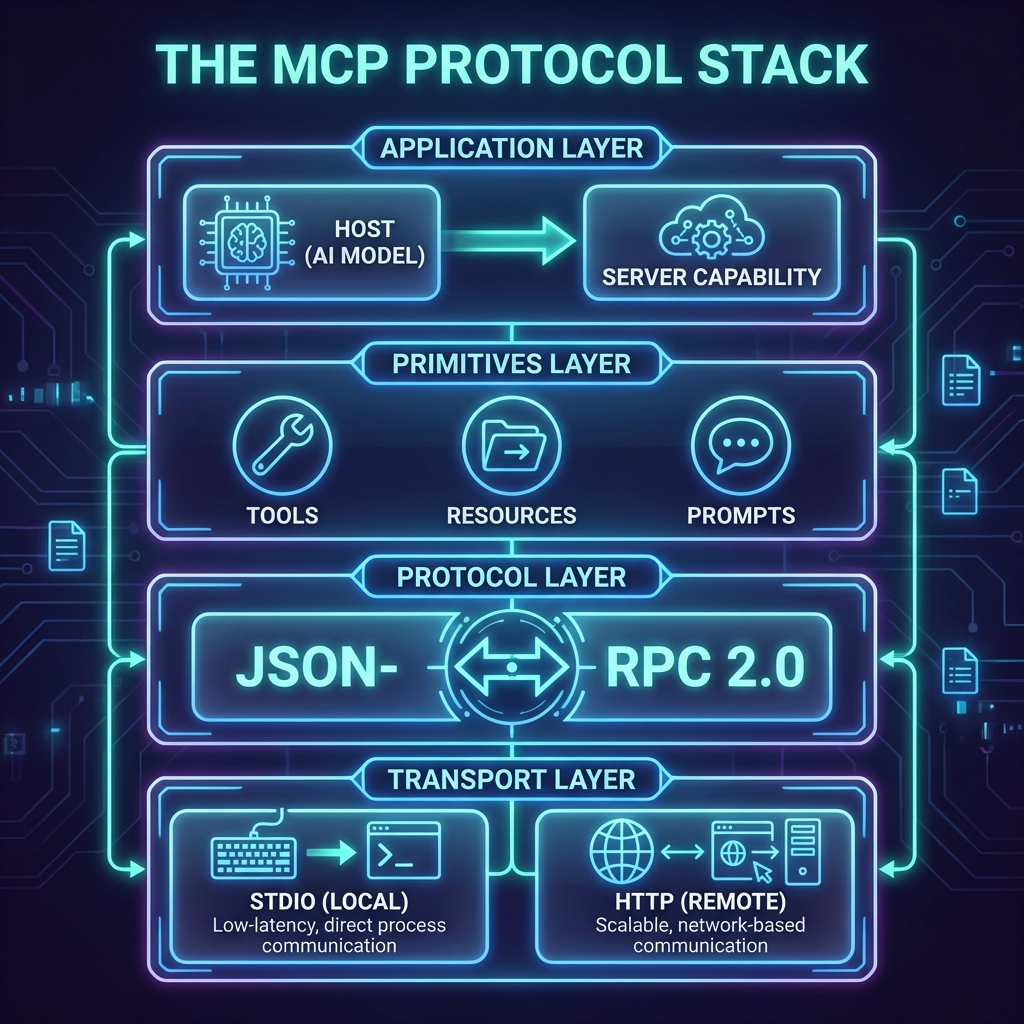

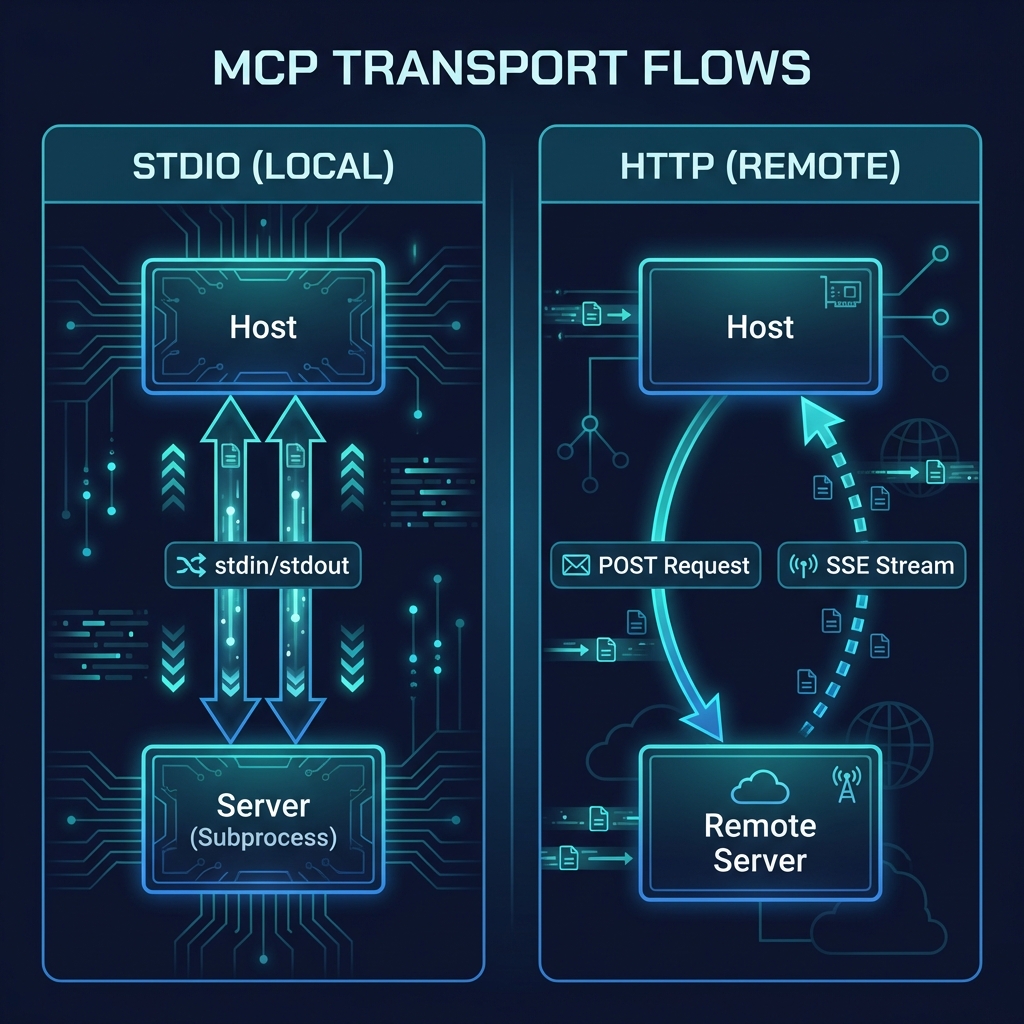

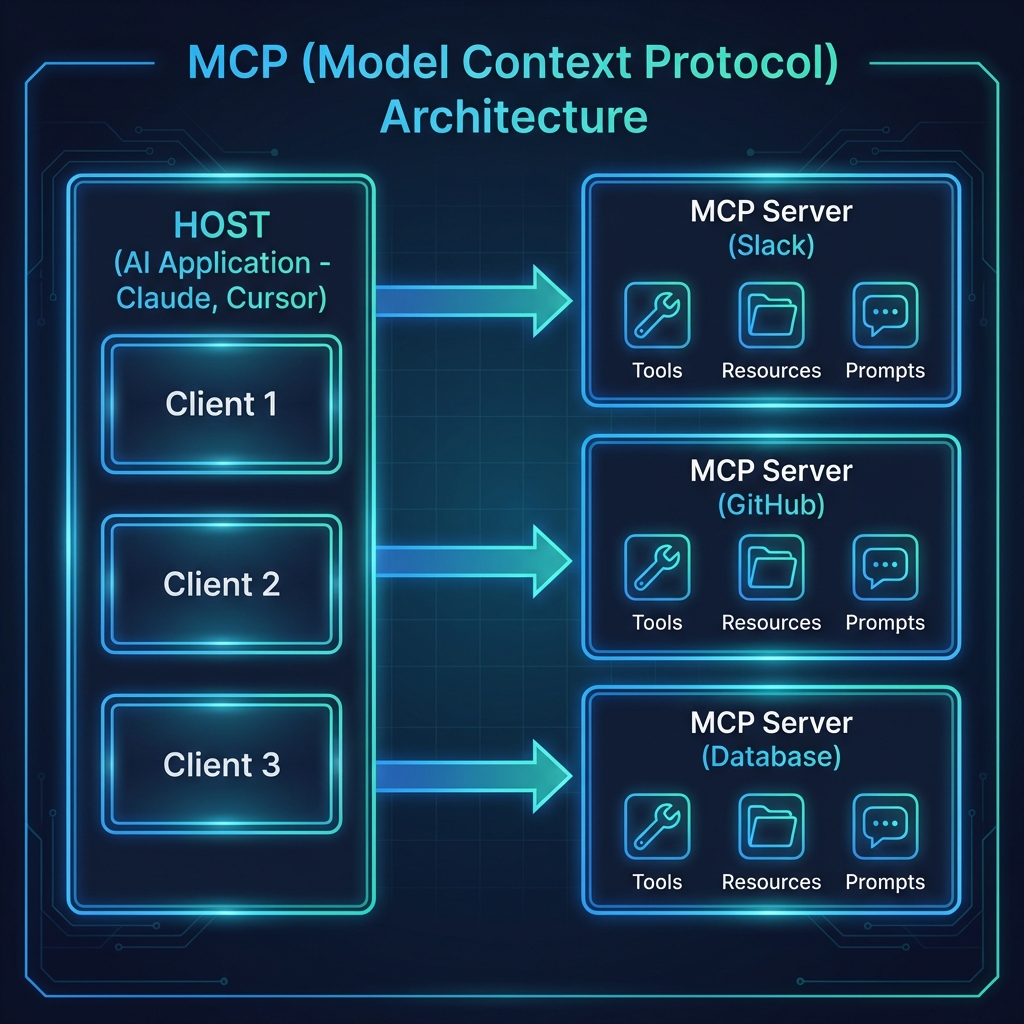

In the [last post](/mcp-architecture), we went deep on how MCP works—the protocol handshake, JSON-RPC messages, and transport layers. Now it’s time to get our hands dirty.

By the end of this post, you’ll have a working MCP server running on your machine. We’re going with Python because it’s the fastest path to “holy crap, this actually works.”

No frameworks. No boilerplate hell. Just a single file that turns your code into something Claude can actually use.

What We’re Building

We’re creating a Notes Server—a simple tool that lets Claude:

- Save notes with a title and content

- List all saved notes

- Read a specific note by title

- Search notes by keyword

- Delete notes

It’s simple enough to build in 20 minutes, but real enough to teach you everything you need to know about MCP.

Why notes instead of another weather API example? Because notes are stateful. They persist between calls. That’s where MCP starts to get interesting.

Prerequisites

Before we start, make sure you have:

- Python 3.10+ installed

- Claude Desktop or another MCP-compatible client

- About 20 minutes of uninterrupted time

That’s it. No complex setup, no cloud accounts.

Step 1: Set Up the Project

First, let’s create a project directory and install the MCP SDK. We’re using uv because it’s fast and handles virtual environments cleanly:

# Install uv if you haven’t already

# Windows (PowerShell)

irm https://astral.sh/uv/install.ps1 | iex

# macOS/Linux

curl -LsSf https://astral.sh/uv/install.sh | sh

Now set up the project:

# Create project directory

uv init mcp-notes-server

cd mcp-notes-server

# Create and activate virtual environment

uv venv

# Windows

.venv\Scripts\activate

# macOS/Linux

source .venv/bin/activate

# Install MCP SDK

uv add “mcp[cli]”

# Create our server file

# Windows

type nul > notes_server.py

# macOS/Linux

touch notes_server.py

Your project structure should look like this:

mcp-notes-server/

├── .venv/

├── pyproject.toml

└── notes_server.py

Step 2: The Minimal Server

Let’s start with the absolute minimum—a server that does nothing but exist. Open notes_server.py and add:

from mcp.server.fastmcp import FastMCP

# Initialize the MCP server with a name

mcp = FastMCP(“notes”)

if __name__ == “__main__”:

mcp.run(transport=”stdio”)

That’s a valid MCP server. It doesn’t do anything useful yet, but it speaks the protocol.

The FastMCP class handles all the protocol machinery—handshakes, message routing, capability negotiation. We just need to tell it what tools to expose.

Step 3: Add State (The Notes Storage)

Before we add tools, we need somewhere to store notes. For simplicity, we’ll use an in-memory dictionary. In production, you’d use a database.

from mcp.server.fastmcp import FastMCP

from datetime import datetime

# Initialize the MCP server

mcp = FastMCP(“notes”)

# In-memory storage for notes

# Key: title (str), Value: dict with content and metadata

notes_db: dict[str, dict] = {}

Step 4: Add Your First Tool

Now the fun part. Let’s add a tool that saves notes:

@mcp.tool()

def save_note(title: str, content: str) -> str:

“””

Save a note with a title and content.

Args:

title: The title of the note (used as identifier)

content: The content of the note

“””

notes_db[title] = {

“content”: content,

“created_at”: datetime.now().isoformat(),

“updated_at”: datetime.now().isoformat()

}

return f”Note ‘{title}’ saved successfully.”

That’s it. One decorator. The @mcp.tool() decorator does several things:

1. Registers the function as an MCP tool

2. Generates the input schema from type hints (title: str, content: str)

3. Extracts the description from the docstring

4. Handles the JSON-RPC wrapper automatically

When Claude calls tools/list, it will see something like:

{

“name”: “save_note”,

“description”: “Save a note with a title and content.”,

“inputSchema”: {

“type”: “object”,

“properties”: {

“title”: {“type”: “string”, “description”: “The title of the note (used as identifier)”},

“content”: {“type”: “string”, “description”: “The content of the note”}

},

“required”: [“title”, “content”]

}

}

The SDK parsed your docstring and type hints to build that schema. No manual JSON schema writing required.

Step 5: Complete the Tools

Let’s add the remaining tools:

@mcp.tool()

def list_notes() -> str:

“””

List all saved notes with their titles and creation dates.

“””

if not notes_db:

return “No notes saved yet.”

note_list = []

for title, data in notes_db.items():

note_list.append(f”- {title} (created: {data[‘created_at’][:10]})”)

return “Saved notes:\n” + “\n”.join(note_list)

@mcp.tool()

def read_note(title: str) -> str:

“””

Read the content of a specific note.

Args:

title: The title of the note to read

“””

if title not in notes_db:

return f”Note ‘{title}’ not found.”

note = notes_db[title]

return f”””Title: {title}

Created: {note[‘created_at’]}

Updated: {note[‘updated_at’]}

{note[‘content’]}”””

@mcp.tool()

def search_notes(keyword: str) -> str:

“””

Search notes by keyword in title or content.

Args:

keyword: The keyword to search for (case-insensitive)

“””

if not notes_db:

return “No notes to search.”

keyword_lower = keyword.lower()

matches = []

for title, data in notes_db.items():

if keyword_lower in title.lower() or keyword_lower in data[“content”].lower():

matches.append(title)

if not matches:

return f”No notes found containing ‘{keyword}’.”

return f”Notes matching ‘{keyword}’:\n” + “\n”.join(f”- {title}” for title in matches)

@mcp.tool()

def delete_note(title: str) -> str:

“””

Delete a note by title.

Args:

title: The title of the note to delete

“””

if title not in notes_db:

return f”Note ‘{title}’ not found.”

del notes_db[title]

return f”Note ‘{title}’ deleted.”

Step 6: The Complete Server

Here’s the full notes_server.py:

“””

MCP Notes Server

A simple server that lets AI assistants manage notes.

“””

from mcp.server.fastmcp import FastMCP

from datetime import datetime

# Initialize the MCP server

mcp = FastMCP(“notes”)

# In-memory storage for notes

notes_db: dict[str, dict] = {}

@mcp.tool()

def save_note(title: str, content: str) -> str:

“””

Save a note with a title and content.

Args:

title: The title of the note (used as identifier)

content: The content of the note

“””

notes_db[title] = {

“content”: content,

“created_at”: datetime.now().isoformat(),

“updated_at”: datetime.now().isoformat()

}

return f”Note ‘{title}’ saved successfully.”

@mcp.tool()

def list_notes() -> str:

“””

List all saved notes with their titles and creation dates.

“””

if not notes_db:

return “No notes saved yet.”

note_list = []

for title, data in notes_db.items():

note_list.append(f”- {title} (created: {data[‘created_at’][:10]})”)

return “Saved notes:\n” + “\n”.join(note_list)

@mcp.tool()

def read_note(title: str) -> str:

“””

Read the content of a specific note.

Args:

title: The title of the note to read

“””

if title not in notes_db:

return f”Note ‘{title}’ not found.”

note = notes_db[title]

return f”””Title: {title}

Created: {note[‘created_at’]}

Updated: {note[‘updated_at’]}

{note[‘content’]}”””

@mcp.tool()

def search_notes(keyword: str) -> str:

“””

Search notes by keyword in title or content.

Args:

keyword: The keyword to search for (case-insensitive)

“””

if not notes_db:

return “No notes to search.”

keyword_lower = keyword.lower()

matches = []

for title, data in notes_db.items():

if keyword_lower in title.lower() or keyword_lower in data[“content”].lower():

matches.append(title)

if not matches:

return f”No notes found containing ‘{keyword}’.”

return f”Notes matching ‘{keyword}’:\n” + “\n”.join(f”- {title}” for title in matches)

@mcp.tool()

def delete_note(title: str) -> str:

“””

Delete a note by title.

Args:

title: The title of the note to delete

“””

if title not in notes_db:

return f”Note ‘{title}’ not found.”

del notes_db[title]

return f”Note ‘{title}’ deleted.”

if __name__ == “__main__”:

mcp.run(transport=”stdio”)

That’s under 110 lines of code. Five tools. A complete MCP server.

Step 7: Test the Server

Before connecting to Claude, let’s verify the server works. The MCP SDK includes a development server:

uv run mcp dev notes_server.py

This starts an interactive inspector where you can test your tools manually. You’ll see all five tools listed, and you can call them with different inputs.

Step 8: Connect to Claude Desktop

Now let’s connect our server to Claude Desktop.

Open Claude Desktop’s configuration file:

- Windows: %APPDATA%\Claude\claude_desktop_config.json

- macOS: ~/Library/Application Support/Claude/claude_desktop_config.json

Add your server configuration:

{

“mcpServers”: {

“notes”: {

“command”: “uv”,

“args”: [

“–directory”,

“C:/path/to/mcp-notes-server”,

“run”,

“notes_server.py”

]

}

}

}

Important: Replace C:/path/to/mcp-notes-server with the actual path to your project directory. Use forward slashes even on Windows.

Restart Claude Desktop. You should now see a hammer icon (🔨) indicating MCP tools are available.

Step 9: Use It

Open Claude Desktop and try these prompts:

“Save a note called ‘Meeting Notes’ with the content ‘Discussed Q1 roadmap. Action items: review budget, schedule follow-up.’”

Claude will call your save_note tool and confirm the save.

“What notes do I have?”

Claude calls list_notes and shows your saved notes.

“Search my notes for ‘budget’”

Claude calls search_notes and finds the matching note.

It works. Your Python functions are now accessible to an LLM. That’s MCP in action.

What Just Happened?

Let’s break down the flow:

1. Claude Desktop spawns your server as a subprocess

2. Protocol handshake happens automatically (remember Blog 2?)

3. Claude queries tools/list and discovers your five tools

4. When you ask about notes, Claude decides which tool to call

5. Your Python function runs, returns a string

6. Claude incorporates the result into its response

You didn’t write any JSON-RPC handlers. No WebSocket code. No API routes. The SDK handled all of that.

Adding a Resource (Bonus)

Tools are great for actions, but what about data that should be pre-loaded into Claude’s context? That’s what Resources are for.

Let’s add a Resource that exposes all notes as a single document:

@mcp.resource(“notes://all”)

def get_all_notes() -> str:

“””

Get all notes as a single document.

“””

if not notes_db:

return “No notes available.”

output = []

for title, data in notes_db.items():

output.append(f”## {title}\n\n{data[‘content’]}\n”)

return “\n—\n”.join(output)

Now Claude can read notes://all to get context about all your notes at once, without needing to call list_notes and read_note multiple times.

Common Gotchas

Print statements break stdio transport

If you add print() statements for debugging, they’ll corrupt the JSON-RPC stream. Stdio uses stdout for protocol messages—your prints hijack that.

Use logging instead:

import logging

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.DEBUG)

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

# This is fine

logger.debug(“Processing request…”)

Type hints matter

The SDK generates input schemas from your type hints. If you write:

def save_note(title, content): # No type hints

The schema won’t know what types to expect. Always annotate your parameters.

Docstrings are your API docs

The docstring becomes the tool description that Claude sees. Write clear descriptions—the LLM uses them to decide when to call your tool.

What’s Next?

You’ve built your first MCP server. In Blog 4, we’ll look at real-world patterns—how companies are using MCP to connect everything from Slack to databases to proprietary internal systems.

The notes server is a toy. But the pattern is universal: expose functions as tools, expose data as resources, let the LLM orchestrate.

This is the third post in a series on MCP. Here’s what’s coming:

1. ✅ This Post: Why MCP matters

2. ✅ Blog 2: Under the Hood—deep dive into architecture, transports, and the protocol spec

3. ✅ Blog 3: Build Your First MCP Server in 20 minutes (Python/TypeScript)

4. Blog 4: MCP in the Wild—real-world patterns and use cases

5. Blog 5: Security, OAuth, and the agentic future

—

For the official MCP examples, see the [quickstart-resources repo](https://github.com/modelcontextprotocol/quickstart-resources) and the [SDK examples](https://github.com/modelcontextprotocol/python-sdk/tree/main/examples).